Hello fellow adventurers,

today we are going to review Keyforge the Unique Deck Game (UDG) by Richard Garfield and Fantasy Flight Games. I spent quite a bit of time thinking about the core concept of unique card games and some of Keyforge’s new and exciting mechanics.

If you prefer to listen to my review, I have also recorded a podcast episode about Keyforge.

Introduction

Keyforge Product Overview (Source: Fantasy Flight Games)

For those of you who don’t know Keyforge or didn’t have the chance to play it yet, let me briefly explain what the core concept of the game is:

The game was designed by Richard Garfield and is published by Fantasy Flight Games. Keyforge is a competitive card game in which players take on the role of an Archon. The innovation Richard Garfild came up with is indeed a unique idea. Because Keyforge is the first Unique Deck Game (UDG). That means each Archon deck is one-of-a-kind. No other player in the world will have the same deck. But how is that possible you may ask? Our mindset of traditional TCGs tells us that every other player could trade or acquire the same set of cards to build the same deck. But in Keyforge there is no deckbuilding. The deck you buy is not only unique in its card composition. It is also ready to play.

Each deck is made up of three factions, and a selection of 12 cards for each faction. Altogether there exist 7 factions and there are something like 50+ cards for each fraction. If you are interested in faction design in card games check out podcast episode #10 for more insights.

In addition to its unique card composition, each Deck in Keyforge has also an individualized name for the Archon who the deck belongs too and a unique procedurally generated graphic which appears on the back of every card. That means every composition of a deck is unique. Fantasy Flight Games claims that there are 104 quadrillion possible 37-card decks. And remember, unlike in Magic you as a player are not allowed to change the composition of cards in your deck. There is no deckbuilding at all. You open your 37 card Deck and are ready to play.

The goal of the game is to use your cards to collect AEmber, which is the resource of the game. The Aember you collect is then used to forge keys. The first player who forges his third key wins the game on the spot. The interesting part is you do not have to kill your opponent as in most other competitive games. That means there is no such thing as life points. Your only goal is to forge 3 keys before your opponent does.

The concept of unique games

Let’s start to analyze the idea of unique games in general.

Richard Garfield gave a very interesting interview on the Fantasy Flight Games Website. In the interview, he talked about his idea behind the concept of unique games. He first started thinking about unique decks in the 90s. He was fascinated by the idea that every player could own something unique. When Magic came out in the 90s internet was not what is today. There was no netdecking and all the information about Magic came from Magazines like The Duelist, Inquest or Kartefakt. It was way more fun back than exploring all the available cards while opening your packs and playing with them. Today everyone knows all the cards before the pre-release from looking through the spoiler list. It is always common knowledge which cards and decks are the top of the pop in the current meta. With unique decks, Richards Garfields intention was to bring back some of the excitement from TCGs before the internet took over the world.

While the idea makes a lot of sense from a design perspective it also creates massive challenges. Let’s go through them quickly.

Challenge 1: Deck Creation and Algorithm

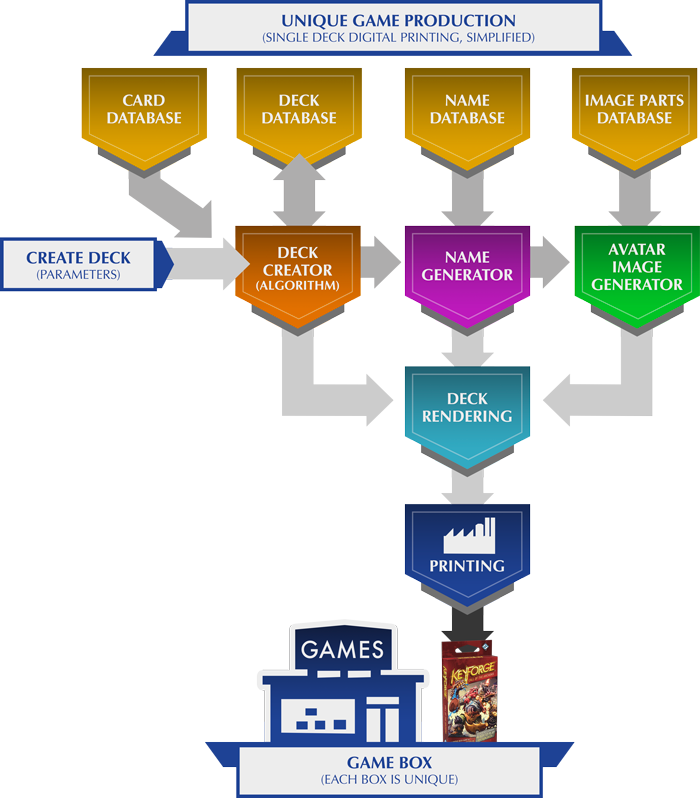

First and foremost, I find it incredibly funny and almost grotesque that the technical progress Richard Garfield wants to overcome here in form of the internet is also the solution for one of the biggest problems of Unique Games. The creation and rendering process of unique games. Without the immense processing power of today’s computers, the rendering of the unique decklists and artworks would not have been possible. The internet plays also a vital role as you can register your decks to your account using a QR-Code printed on a card in every pack.

The main challenge from a game design perspective is the creation of the decks. How can you make sure every instance of a deck is playable. How do you make sure the decks are fun to play? And how do you balance them? I don’t know what the core design principles of Keyforge where, but I am sure one the goals must have been to make the game playable with a wide range of decks. And this is only possible if the rules and interactions are simple enough. Compared to other TCGs I think there is less design space for very complex and unique card designs. In Magic, for example, are a lot of cards that can make only sense in some very specific deck compositions. These cards are borderline unplayable in 99% of the decks, while they shine in the remaining 1% of the decks. A card like this nothing you could ever print in a unique game. So the main design challenge is to create a ruleset that supports a wide range of combinable mechanics in order to create at least playable decks. But if you think about magic, these extraordinary cards with these fringe use cases are often the cards players engage the most with. So if you want to have these more complex combo like cards in a unique game you need some kind of algorithm that makes sure that some cards are only combined with other cards in a certain way. That means if you have a card that cares about a specific creature type. Wouldn’t it be incredibly unsatisfying to have a card that cares about knights in your deck but your deck does not contain any. This is exactly what the Keyforge algorithm takes care off. It ensures that cards that are meant to be combined do at least have a certain threshold of other cards that could be combined with it.

Individual cards could, in some cases, have down-stream dependencies, such as [If X is selected for Pool1, then draw either a, b, or c from Pool2; In the Knight example, the algorithm could take care that your deck at least has 4 knights in it. In addition, a database of product instances needs to be maintained to ensure each new instance of a deck is a unique one.

Keyforge Production Process & Algorythm (Source: Fantasy Flight Games)

Challenge 2: Production, Rendering & Printing

Other challenges come from printing and production. Conventional offset printing possibilities are not feasible here. And how would the physical collation happen? It cannot be random. It is bound to the algorithm. Each deck contains a unique card back with a unique graphic, a unique name and a unique combination of house cards. The Software needs to handle not only the algorithm of item sequence but also random name generation and a procedurally generated unique image, all of which would need to be automatically collated and prepared for output. Fantasy Flight Game mentioned in an article that these facts caused a lot of headaches regarding the computing power of the rendering process. I think at one point in time they needed 166 days to render 100.000 decks.

Printing is also more expensive as it requires digitally printed cards instead of offset printing which is in general 2-4 times more expensive and way slower. I have read rumors that the game is probably printed in Germany.

Keyforge Procedurally Generated Back (Source: Fantasy Flight Games)

Challenge 3: Flavor

The next challenge is flavor. The randomness leads to the necessity to combine different factions and cards. It is therefore very difficult to transport flavors and story within a deck. There is no such thing as a themed Goblin Deck. Richard Garfield mentioned that it was required by game design to work with a variety of different factions that could be mixed and matched. If you think about that from a narrative aspect it is quite difficult to find reasons why all of these different factions and cards should sometimes work together and sometimes not. I personally don’t like the flavor of Keyforge. I don’t like the artwork. The story is almost non-existent and I don’t think this will change in the future. Maybe it is just impossible to create a very large amount of possible decks and a compelling story at the same time.

Challenge 4: Balancing

One of the biggest worries I’ve heard and read about over and over again is balancing. With 104 quadrillion decks, how can you make sure that all decks are roughly equal in power? The truth is. You can’ t. And the developers knew that. Richard Garfield wrote a nice short story of balancing on board game geek.

The core message is: Instead of making decks fair. They chose the approach of making as many decks as possible playable and fun against each other. They accepted the fact that decks will have different power levels. To some degree, the different power levels can be compensated by variance and player skill, but only to some degree. Therefore, Fantasy Flight Games came up with a nice balancing idea of putting “chains” on the favored deck. Chains are some kind of handicap mechanic designed to balance out stronger decks. Basically, each chain costs a deck one (or sometimes more) cards over the course of the game. I have not played Keyforge on a tournament, but I like the idea of chains. And I also like the fact that they did not try to make decks equally powerful because I don’t think this is possible. However, I am worried about the emotions that players have when they open a deck that is more or less garbage. Yes, they could play that deck against another deck and give the other deck some chains, but I still don’t like the disappointment you get when opening a bad deck. But you could compare that with opening a bad booster pack in a TCG I guess.

Advantages of Unique Deck Games compared to CCGs, TCGs, and LCGs

One advantage of a unique card game is that you do not have to be as strict with the identity of color or faction as for example in magic.

Richard Garfield described this as follows: “If you’re going to have factions in games where a player can choose the cards they want to play with, you must be very careful not to bleed the powers from one faction to another. If you put a few cards in the wrong place—even if those cards are technically rare—players might choose to play with them a lot.

On the other hand, with a UDG you can have a House with, for example, a few big creatures but predominantly small creatures. The House will have the character you would expect—mostly small creatures with some exceptions. This makes designing Houses feel much more like designing characters rather than simply dividing up powers between factions.“

I think the concept of a unique deck game is very innovative. However, I think it is very difficult to compare it with TCGs, CCGs or LCGs. It is by no means a direct improvement or a successor. Rather, I have the feeling the target audience is a slightly different one. For some people, it is a no-go that they are not able to customize their own deck. For others, this is almost a relieve as they simply don’t have the time to think about deck building and acquireing the required cards on the secondary market. From my perspective, Unique Deck Games are just at their beginning. And with new innovations with regard to printing and the algorithms I think there is more to come. However, at the current point in time, I think it is significantly more complex to create a unique deck game compared to a traditional CCG.

Keyforge as a Game – Reviewing Game Mechanics

We now talked quite a bit about the core concept of unique deck games. Let’s dive a little deeper into Keyforge and its mechanics now. Maybe we can find some inspiration for our games.

The essential question the game poses to the players is:

How can you forge 3 keys before your opponent does?

Keyforge Keys Tokens

To answer this question the most important player skill is to understand their deck and implement the correct strategies to acquire Aember and prevent the opponent from forging keys.

There are no alternative win or loss conditions (No player life points, you do not lose when your deck of cards is empty). The only goal is to acquire enough AEmber to forge your 3 keys before your opponent does.

To forge a key you must start a turn with at least six pieces of Æmber. Once a player has created a third key the game immediately ends.

Each player starts the game with a deck of 36 cards. Each deck always consists of 3 factions and 12 cards per faction. The different card types are:

Actions: which are typically one time effects

Artifacts: which are permanent effects that stay in play and can be used repeatedly

Creatures: which are used to reap Aember and fight opposing creatures and

Enhancements: which are permanent improvements that are attached to creatures on the battlefield. 0

A turn consists of 5 Phases:

1 Forge a key if you control at least 6 Aember.

2 Choose one of your three houses

3 Play, discard, and use cards of the chosen house.

4 Ready cards

5 Draw cards up to your hand size (standard is 6 cards)

House Choice

Keyforge Houses and Factions (Source: Fantasy Flight Games)

The most important decision every round is the house choice. The chosen hoise determines not only which cards you can play from your hand but also the cards you can use on the battlefield. It is very important to understand that cards have no playing costs. Let me say this again. There is no mana, stamina or whatsoever cost for playing a card from your hand.

You can play cards from your hand that correspond with the chose faction, as well as activate those cards already in play from the nominated faction. Cards have a broad range of effects, some of which are resolved when they come into play, while others are utilised through being activated or fulfilling certain criteria.

From a game designers perspective that feels incredibly scary, because you lose your main card balancing ability by not using a resource. This was probably the aspect of the game that I was most suspicious about.

But after playing some games I must say the house choice creates very interesting Trade-Offs. Trade-Offs between your board which is often not represented equally in all houses and your hand which is also not equally distributed in your houses. To make that crystal clear. If you chose one house because you have three cards in hand of that house you would like to play, but your creatures in play are from another house, you cannot use these creatures during that turn. That means you often have to decide between developing your board and using your board. In the games I have played this mechanic has proven itself to be a great comeback mechanic. Often a player was way ahead on board. But as his hand was mostly stuck with cards from other houses the player wasn’t able to develop the board further.

Sometimes there is an obvious house choice. But most of the time at least two of the houses have arguments for choosing them during a turn. The result is that players have a lot of agency in how to play a deck. From the few games I’ve played, it felt like the decks had more variety of gameplay than a very streamlined magic deck. By focusing on the different Houses in their decks in different ways, it can almost be like playing a different deck.

There are some cards can interact with house choice. For example, restricting or forcing a specific house choice from your opponent. I like this implementation a lot. Why? Because it creates interesting choices. You as a player do have some information which house could be the best choice for your opponent based on the current board state. But there is also hidden information, the oppenents hand. You have to make a decision under uncertainty. You cannot control the entire turn of your opponent, but your decisions can still have a major impact on the opponent’s strategy.

The entire mechanic of choosing a house leads to an aspect of the game that is not immediately apparent. Hand crafting.Hand crafting is acutally a big aspect of the game. Throughout the game you are managing your cards and trying to craft a hand for different situations or for a good combination of cards (this can be specific combos or simply many cards of a specific faction).

On the other hand, it can feel sometimes very annoying if you can only use some of your resources. For me, it was frustrating that I never had the chance to combine the spell of one house with a creature of another house in one turn.

To mitigate that feeling, some cards have the ability “omni”. That means you may use that card even if the card does not belong to the active house.

Altogether I like the mechanic of choosing a house.

Resource System – Aember

Let’s talk a little bit about the resource system.

Aember really is only required to forge keys. You don’t need it to play or activate cards.

You can get Aember in different ways.

- Reap: Any ready creature of the active house may reap. When a creature is used to reap, its controller gains 1 Æmber for their Æmber pool.

- Amber Bonus: Many cards in the game have an Æmber bonus. When a card with an Æmber bonus is played, the player gains that much Æmber

- Steal: Some Cards have the ability steal: When an ability steals Æmber, the stolen Æmber is removed from the opponent’s Æmber pool and added to the Æmber pool of the player resolving the steal ability.

- Capture: Some Cards have the ability capture:

Captured Æmber is taken from an opponent’s Æmber pool and placed on a creature controlled by the capturing player. Players may not spend captured Æmber. When a creature with Æmber on it leaves play, the Æmber is placed in the opponent’s Æmber pool.

It is always obvious for both players how much amber the opponent has and whether he will forge a key in the next turn. What really comes into play here is the order of a turn. I think the turn order was chosen wisely by the developers. The keys are forged at the beginning. As a player you ask your opponent the question during your turn: I have more than 6 AEmber. Can you somehow prevent me from getting a key next turn? The opponent then has exactly one round of time to interact with the opponent’s amount of Aember.

I like that there are different mechanics interacting with the Aember Pool. It always feels like a back and forth between the players. All the game components, especially creatures and spells feel well integrated into the theme of acquiring Aember. If you have captured a lot of Aember which is stored on a creature until the creature dies, the entire game can revolve around the question of whether you can keep that creature alive or not.

Combat

This brings us to combat. Combat is quick, simple, and usually deadly. “When a creature

is used to fight, its controller chooses one eligible creature controlled by the opponent as the target of the attack. Each of the two creatures deals an amount of damage equal to its power to the other creature. All of this damage is dealt Simultaneously.”

Armor gives your creature some points of protection against incoming attacks each turn. Health and Attack Power are a shared stat. This means a creature with Attack 4 has also 4 Hit Points. When a creature takes an amount of damage equal to ist attack value it dies. However, damage on a creature does not reduce its power. If a creaturewith 4 power got 3 damage, the damage sticks, but the power is still 4. This means taking damage does not cause any consequences until it is lethal. For me, the combat system is fine but almost a bit too simple. I don’t like the fact that I have no possibility to interact during the combat step. No instants nothing. Combat is entirely deterministic and feels more like a puzzle. There is no risk of failure. But no risk also means no tension.

Elusive:

The first time a creature with the elusive keyword is attacked each turn, it is dealt no damage and deals no damage to the attacker in the fight.

SKIRMISH:

When a creature with the skirmish keyword is used to fight, it takes no damage from the opposing creature when the damage from the fight is dealt.

Both of these mechanics require more effort from your opponent to deal with your creature. I like these mechanics a lot. It helps to protect creatures but does not completely prevent interaction from happening as the abilities “indestructible” or “hexproof” in magic do.

Turn Order & Summoning Sickness

In Magic, there is the annoying topic of summoning sickness. Anyone who has ever explained Magic to a new player knows why it’s a painful topic. Creatures that come into play are not allowed to attack or take actions for one round. However, there is no indication of this on the cards and a creature you just played looks exactly like the creature you played last round. So you have to remember this effect. In addition, artifacts don’t suffer summoning sickness. Except, of course, artifact creatures. All in all very confusing for new players. In Keyforge, creatures and artifacts always come into play tapped or how it is called here exhausted. This immediately gives you a visual hint that you can’t use the creature. Unlike Magic, the untap step is at the end of the turn. This also has an advantage. If the opponent can tap one of your creatures on his turn, it’s not usable for one turn. This effect is also simply visualized by tapping and does not require any extra status cards, tokens or reminders. Of course this would not be possible with Magic, because the concept that the defending player determines the blocks would no longer work. However, for Keyforge the turn order and the usage of tapped and untapped creatures feels way better than in Magic.

While the summoning sickness is really well implemented, the system no longer works without tokens once the stun ability comes into play. When a creature becomes stunned, you have to place a stun status card on it. The next time the creature is used, the only thing that happens is the creature exhausts and the stun card is removed. That means the creature remains stunned until the player chooses the respective house and uses an entire action to remove the stun effect. I like the aspect that you always have a negative effect from the stun. No matter if you choose the house in the next round or not. However, the stun effect somehow feels strange, because it is the only status effect that is marked with a card.

Creature Positioning / Battleline / Flanks

In contrast to Magic, the position of creatures on the playing field plays a role. And the position in the battle line matters much more than I initially expected. Creatures enter play on the flank of the battleline. The creatures on the far right and far left of a player’s battleline are on the flanks of the line. Many cards are restricted to be used on cards that are either on flanks or not on flanks. This creates a nice condition that can be added to cards which then creates interesting decision making for the players. Let’s say you have a removal that kills a creature that is not on a flank, but the most powerful creature of the opponent is currently on a flank. Do you use the removal on a weaker creature or do you keep it in your hand and hope your opponent plays another creature and puts it on the flank you are expecting.

Some cards also refer to neighbors. For example splash damage that deals damage to all the neighbors of a creature.

Other cards allow a player to swap positions in the battleline. There are quite some mechanics that interact with the battleline.

Another one is taunt: If a creature has the taunt keyword, any of its neighbors that do not have the taunt keyword cannot be attacked by an enemy creature that is being used to fight. In the battleline, taunt creatures are slid slightly forward to indicate their presence to the opponent. I like this way of positioning because it is a logical visualization of a creature that is dominant and it again makes another status-token unnecessary. In addition, it is again a mechanic that helps you to protect your most valuable creatures. And it asks an interesting question to your opponent: can you kill both, the taunting creature and my strongest creature in one turn?

Altogether the battleline is a super super simple implementation but affects so many cards and game mechanics. It is maybe not the most innovative implementation, but I like it a lot.

Archives & Hand Management

A player’s archive is a facedown game area. Card abilities are the only means by which a player is permitted to add cards to their archive. During step 2 of a player’s turn, after they select an active house, the active player is permitted to pick up all cards in their archive and add those cards to their hand. The archive is a game mechanic for hand management. Why that you may ask. From a design perspective, the archive serves two purposes. Both by removing cards from the traditional cycle of drawing, playing, discarding and reshuffling in the used cards. First, you can archive away less useful or conditional cards and make it more likely to get the cards you really need after shuffling back in your deck. Second, you can choose to return the archive to your hand allowing you to plan a monster turn where you store pieces of a combo in the archive until you drew the other pieces. It basically ensures a bigger and a specific hand on a future turn.

This mechanic is really well suited to mitigate some of the randomnesses in unique deck games. And I wonder if at some point in time during development archiving was a player ability that could be used as a player action (without the need of a card that lets you archive).

Chains & Balancing

Chains are used in two different ways:

To balance decks; Chains are a way of handicapping a particularly powerful deck or skilled player. By changing a player’s Chain count it changes the number of cards they’re allowed to draw back up to at the end of their turn. It’s a fairly simple, yet elegant solution to the fact that every deck is unique and some may be a bit too overpowered against others.

To balance strong cards:

Keyforge chain tracker card (Source: Fantasy Flight Games)

Some card abilities cause a player to gain one or more chains. If a player gains chains, that player increases their chain tracker by the number of chains gained. If a player has at least one chain when refilling their hand, they draw fewer cards according to the chart below. Then, they shed one chain by reducing the number on their chain tracker by one.

This means you borrow a resource in form of a card from a future turn.

I really like that you are always drawing back up to 6 cards. That means you get access to your entire deck in most games which lets you plan strategically with specific cards in your deck. It also gives you new resources every turn and you never end in a spot where you do not have anything in hand.

Conclusion

I had more fun playing the game than I expected from reading the rules. The rules felt to simple when I first read them. But Keyforge introduces some new game mechanics that make you have to think about new tactics. Board presence isn’t as important as it is in other games. Hand management on the other side is much more important. And the fact that for once you don’t have to attack your opponent’s hit points feels surprisingly different.

I made a list of pros and cons about the game through which I will go no quickly as a conclusion:

Pro:

- The border to enter the game is extremely low. Both money wise and timewise. For less than 10 Euros you get a deck that is ready to play

- In addition, the basic rules of the game are very simple. Much of the complexity is solved by the text on the cards. The game is easy to learn but hard to master.

- Unique deck names are awesome → They remind me of the randomly generated monster names in Diablo. Actually, the unique names play an important role in player engagement with their deck.

- Keyforge is very much about discovery. In the sealed format you start to play a game with an unknown deck. You are not even allowed to lock through your decklist. This creates a very nice aura of the unknown. However, if Fantasy Flight Games wants to keep that discovery moment, they need to produce a lot of new content to keep the players engaged.

- House Choice is a Great Comeback Mechanic. Although it’s actually quite the opposite. The mechanics make sure that a player doesn’t get too far into the lead. It is more an Anti-Lead-mechanic.

- New win condition feels surprisingly different

- Fast gameplay & little downtime. Since you can hardly interact in your opponent’s move, you can plan your own move with half your attention.

- Layout – The cards are well made, and look and feel really nice.

- Chains as handicap mechanic (it is a fantastic idea)

- No netdecking. You can’t just look up what the synergies of your deck are or that the weaknesses are; you will only find out by playing.

Cons:

- Only one win/loss condition

- The combat system is very deterministic

- Artwork / Flavor (but I have also read that people like it so maybe ist just me)

- No deck customization means there is nothing you could really do with the game in between playing sessions.

- Not enough hidden information

- Not enough interaction (no instants)

That’s everything I have to say about Keyforge for now. I am looking forward to play in my first Keyforge torunament this weekend. I hope you enjoyed my first game review from a developers point of view. If you liked it let me know and will do more of them in the future.

Sources:

Richard Garfield on Balancing Keyforge

Richard Garfield on Keyforge Game Design

Design Article on Unique Deck Games (on FFG)

Keyforge Rules Book

Reddit Post on Keyforge Printing

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.